Wagon Preachers: The Revolutionary Ministers of the Underground Railroad

The dusty roads of America's troubled past were traversed by unsung heroes who carried both the word of God and the torch of freedom. These men—wagon preachers—navigated the dangerous terrain of slavery-era America, their humble carriages disguised as vessels of spiritual salvation while secretly harboring a revolutionary purpose.

The Sacred Journey of Courage

They called them wagon preachers—fearless ministers who transformed simple horse-drawn carriages into mobile sanctuaries of hope and resistance. These were men who risked everything—their freedom, their safety, and their very lives—to serve a higher calling. These circuit riders moved between plantations and settlements, their arrival signaling more than just Sunday service. For enslaved African Americans, the wagon preacher's appearance meant potential liberation—a connection to an invisible network of freedom that stretched northward toward liberty.

"When the preacher's wagon appeared on the horizon, we knew the Lord was working in mysterious ways," recalled former enslaved person Henry "Box" Brown in his narrative. "Their sermons spoke of Moses leading his people from bondage, but their eyes told us they weren't just talking about ancient Egypt."

The genius of these mobile ministers lay in their ability to hide revolutionary action behind religious authority. White slave owners often permitted religious gatherings, unaware that biblical stories of liberation were coded messages and that prayer meetings served as planning sessions for escape.

Dual Purpose Ministry: Faith in the Face of Danger

These traveling ministers preserved African American religious and cultural traditions during a time when enslaved people were often forbidden from gathering. The penalties for aiding escaped slaves were severe—imprisonment, brutal beatings, and in some cases, death. Yet these courageous men continued their dangerous work, knowing that each sermon could be their last, each journey potentially ending in capture. They taught Biblical literacy when many Black Americans were denied education, and their teachings emphasized dignity and selfhood when society denied both to African Americans.

Reverend John Parker of Ohio exemplified this dual mission. By day, he delivered fiery sermons across Kentucky and Virginia. By night, he ferried freedom seekers across the Ohio River, leveraging his ministerial reputation to move unquestioned through slave territories. When confronted by suspicious authorities, Parker would simply produce his Bible and express concern for "lost souls" in the area.

"I answer to a higher authority than any man's law," Parker reportedly told those who aided him in his clandestine work. His religious conviction provided both motivation and cover for his resistance activities.

Building Networks of Freedom

The unique mobility and respected positions of wagon preachers made them instrumental in maintaining connections between scattered African American communities. Their regular movement between communities made them less suspicious to authorities, allowing them to:

- Pass crucial information about slave patrols and safe routes

- Connect separated families with news of loved ones

- Coordinate escape attempts with precise timing

- Memorize and share maps of safe houses along freedom routes

- Transport documents and passes for those seeking freedom

Reverend Josiah Henson, who escaped slavery in 1830, became a celebrated wagon preacher in Canada while helping guide over 100 enslaved people to freedom. His autobiography later inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe's character Uncle Tom (though Henson's actual life was one of courage and resistance, unlike the fictional character that came to bear negative connotations).

Legacy of Resistance

The legacy of Black wagon preachers extends beyond the Underground Railroad. These ministers established some of the first independent Black churches in America—institutions that would later serve as foundations for civil rights activism.

Leonard Grimes worked as a wagon preacher in Virginia while secretly transporting enslaved people to freedom. He was eventually caught and imprisoned for his Underground Railroad activities but later became a prominent abolitionist minister in Boston, where he established the Twelfth Baptist Church, known as "The Fugitive Slave Church" for its congregation of formerly enslaved people.

Daniel Coker founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore, creating not just a house of worship but a community center where freed and enslaved Black people could learn to read, write, and organize. His wagon routes became mapping points for future AME churches across the Mid-Atlantic.

Art and Remembrance

The wagon preacher tradition has been immortalized in Black American art, particularly in the works of Jacob Lawrence, whose "Migration Series" captures the movement and spirit of Black religious leaders guiding their communities toward freedom. Contemporary artist Theaster Gates has incorporated wagon preacher traditions into his installations, transforming ordinary vehicles into symbols of spiritual and physical liberation.

"We preached heaven on Sunday and delivered earthly freedom on Monday," wrote James W.C. Pennington, a formerly enslaved man who became a celebrated wagon preacher after his escape. His circuits through Pennsylvania and New York helped establish safe houses that would shepherd thousands toward freedom.

Courage That Changed America

The extraordinary bravery of wagon preachers cannot be overstated. They operated in plain sight while conducting some of the most dangerous resistance work possible. Many were captured, some were killed, and others lived with the constant threat of betrayal. Their courage wasn't just about personal bravery but reflected a moral conviction that freedom was worth any price.

"Every time I climbed onto my wagon seat, I knew it might be my last journey," wrote one anonymous preacher whose diary was discovered decades after the Civil War. "But the faces of those I helped toward freedom gave me strength that no fear could diminish."

The Enduring Tradition: Faith and Resistance Across Generations

These revolutionary men of faith established a powerful tradition where spirituality and resistance became inseparable forces in Black American history. Their example reveals a profound truth: in the African American experience, authentic faith has consistently manifested as active resistance against oppression.

This sacred connection between faith and liberation continued through each era of the struggle for equality:

During Reconstruction, AME Church leaders like Bishop Henry McNeal Turner advocated for Black political rights and economic independence, building on the foundation laid by wagon preachers. In the early 20th century, religious leaders like Ida B. Wells merged faith with journalistic activism to combat lynching and racial violence.

The Civil Rights Movement saw this tradition reach new heights, with Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, and Reverend Ralph Abernathy leading faith-centered nonviolent resistance. Their churches, like those established by wagon preachers, became centers for organizing, training, and spiritual renewal in the face of brutal opposition.

More recently, faith leaders like Reverend William Barber II with the Poor People's Campaign and clergy who stood with protesters in Ferguson and Minneapolis continue this sacred tradition—leading with moral clarity against systems of injustice while drawing spiritual strength from the same source that empowered those early wagon preachers.

The Continuing Journey

Their legacy reminds us that freedom has always required both deep faith and bold action—a wagon moving steadily forward, carrying precious cargo toward liberation. The connection between spiritual conviction and liberation work wasn't unique to the Underground Railroad era but represents a continuing thread in Black American history.

Today, as new challenges to freedom and dignity emerge, we need faith leaders who embody this dual commitment—speaking truth from pulpits while taking action in communities. The wagon preachers remind us that true ministry has always meant addressing both spiritual needs and earthly injustice, a tradition that must continue if we are to complete the journey toward full liberation that those courageous ministers began generations ago.

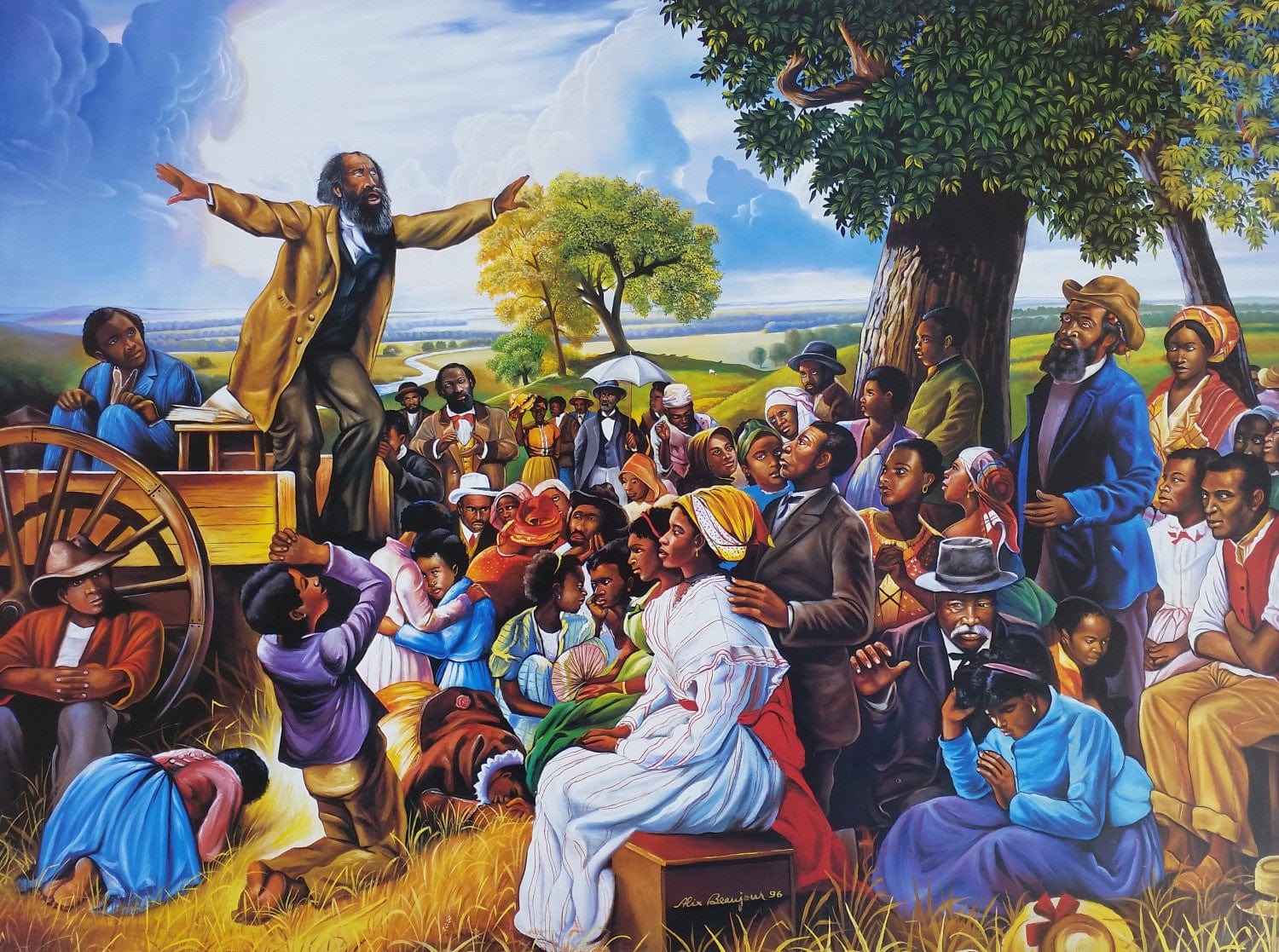

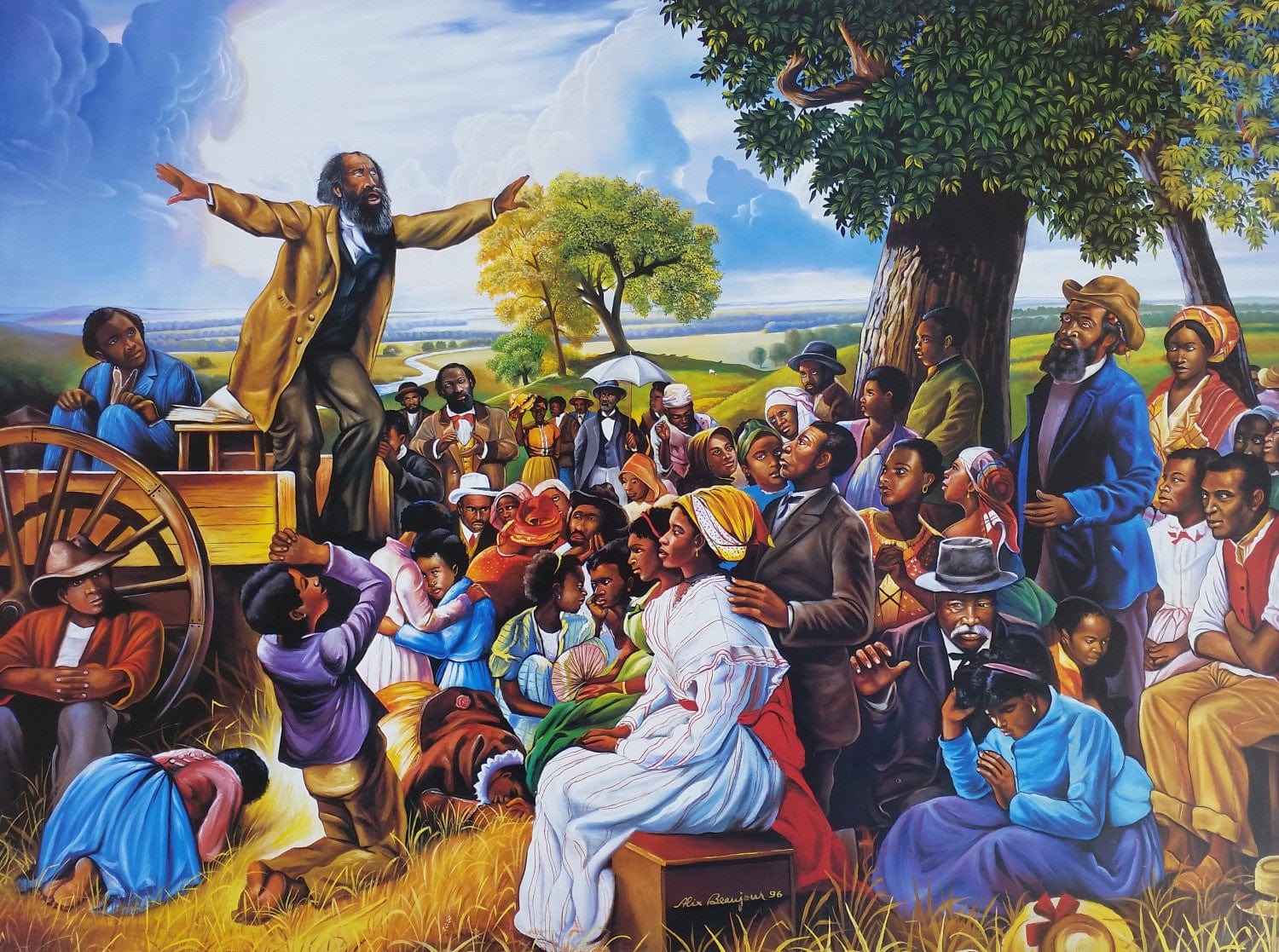

Featured Art

Wagon Preacher by Alix Beaujour

This powerful artwork captures the courage and faith of wagon preachers who risked everything to bring both spiritual salvation and physical freedom to enslaved African Americans. Beaujour's masterful depiction reminds us of these unsung heroes of American history.

Shop NowSources: Historical accounts from Henry "Box" Brown's narrative, James W.C. Pennington's writings, Josiah Henson's autobiography, and archives from the AME Church Historical Society.